TITLES OF NOBILITY ACT or NESARA

THE ORIGINAL 13TH AMENDMENT

Most people do not realize that the well-known thirteenth amendment - that which ended slavery in America - was not the first "Thirteenth" amendment proposed. As any Constitutional scholar (or anyone remotely familiar with American History) can readily tell you, the thirteenth amendment to the United States Constitution is an important one. Perhaps even the most important one of all. As most students learned at some point in school but quickly forgot, the thirteenth amendment that is so well known today was ratified by congress in 1865, and effectively abolished slavery in the United States.

While this amendment didn't exactly end racism once and for all (it’s proven rather difficult to make laws to that effect), it certainly was quite an important step in that direction.

But the true history of the thirteenth amendment actually goes back much farther than The Civil War, and has very little to do with slavery.

The story begins in 1789, sixty-six years before slavery would be abolished.

There was a young woman from Baltimore, Ms. Betsy Patterson. This young lady, in some kind of flight of youthful fancy, moved to England, where she married Napoleon Bonaparte's younger brother, Jerome, and with him had a child, young Jerome Napoleon Bonaparte (the young couple were clearly not known for coming up with clever names). Now, because of his mother's heritage, this child by law was granted automatic citizenship into the United States, while at the same time retaining a status of nobility in France, being Napoleon's nephew and all.

There were many among the nobles in America who viewed this as a travesty to their own national identity, and quite a good reason to add a little something to the Constitution that was apparently missing.

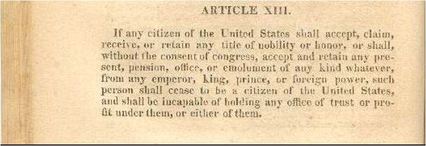

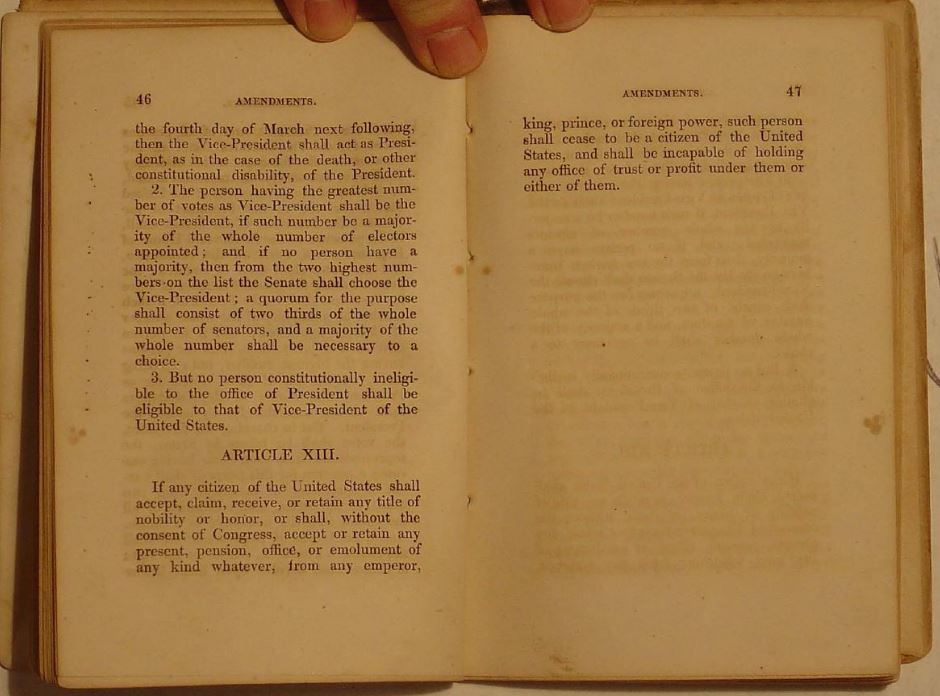

And thus was born the Titles of Nobility Act; a proposed constitutional amendment (it would be, of course, the 13th) stating that any citizen of the U.S. who receives a title of nobility or honor from a foreign nation without the consent of congress must be forced to give up his or her citizenship in the United States.

Apparently, the proposed amendment must have sounded quite good to Congress at the time, as it passed quickly through both houses by quite a wide majority, then was sent down to the individual state legislatures to be voted on (as article 5 of the constitution requires). It is here that the amendment finally found trouble.

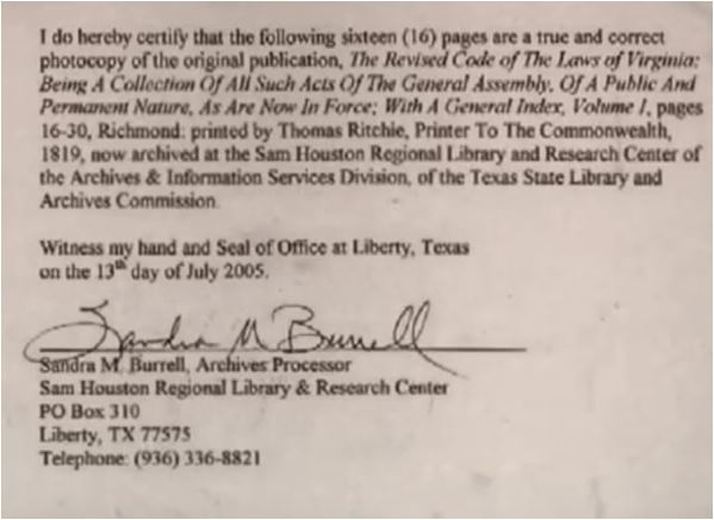

As is shown in the above document (you may have to pull it down to view) the original 13th Amendment was ratified by Virginia and added to their Constitution upon its revised printing on March 12, 1819. To view that entry, you will have to scroll close to the very end of the document above from the Virginia General Assembly. Don't miss the certification of the 13th Amendment original document above.

In closing, here are just a few of the many people who would lose their citizenship should such an amendment go into effect today: George H.W. Bush, Norman Schwarzkopf, Rudy Giuliani, and even Bill Gates; for all of these men have one important thing in common: they have been granted honorary knighthood from Britain.

While this amendment didn't exactly end racism once and for all (it’s proven rather difficult to make laws to that effect), it certainly was quite an important step in that direction.

But the true history of the thirteenth amendment actually goes back much farther than The Civil War, and has very little to do with slavery.

The story begins in 1789, sixty-six years before slavery would be abolished.

There was a young woman from Baltimore, Ms. Betsy Patterson. This young lady, in some kind of flight of youthful fancy, moved to England, where she married Napoleon Bonaparte's younger brother, Jerome, and with him had a child, young Jerome Napoleon Bonaparte (the young couple were clearly not known for coming up with clever names). Now, because of his mother's heritage, this child by law was granted automatic citizenship into the United States, while at the same time retaining a status of nobility in France, being Napoleon's nephew and all.

There were many among the nobles in America who viewed this as a travesty to their own national identity, and quite a good reason to add a little something to the Constitution that was apparently missing.

And thus was born the Titles of Nobility Act; a proposed constitutional amendment (it would be, of course, the 13th) stating that any citizen of the U.S. who receives a title of nobility or honor from a foreign nation without the consent of congress must be forced to give up his or her citizenship in the United States.

Apparently, the proposed amendment must have sounded quite good to Congress at the time, as it passed quickly through both houses by quite a wide majority, then was sent down to the individual state legislatures to be voted on (as article 5 of the constitution requires). It is here that the amendment finally found trouble.

As is shown in the above document (you may have to pull it down to view) the original 13th Amendment was ratified by Virginia and added to their Constitution upon its revised printing on March 12, 1819. To view that entry, you will have to scroll close to the very end of the document above from the Virginia General Assembly. Don't miss the certification of the 13th Amendment original document above.

In closing, here are just a few of the many people who would lose their citizenship should such an amendment go into effect today: George H.W. Bush, Norman Schwarzkopf, Rudy Giuliani, and even Bill Gates; for all of these men have one important thing in common: they have been granted honorary knighthood from Britain.

MONROE DOCTRINE

TO READ, PLEASE USE THE SLIDE BAR TO THE RIGHT

Fake 13th Amendment

December 6, 1865

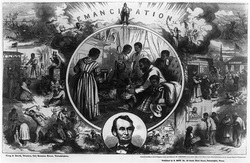

On this day in 1865, the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, officially ending the institution of slavery, is ratified. "Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction." With these words, the single greatest change wrought by the Civil War was officially noted in the Constitution.

The ratification came eight months after the end of the war, but it represented the culmination of the struggle against slavery. When the war began, some in the North were against fighting what they saw as a crusade to end slavery. Although many northern Democrats and conservative Republicans were opposed to slavery's expansion, they were ambivalent about outlawing the institution entirely. The war's escalation after the First Battle of Bull Run, Virginia, in July 1861 caused many to rethink the role that slavery played in creating the conflict. By 1862, Lincoln realized that it was folly to wage such a bloody war without plans to eliminate slavery. In September 1862, following the Union victory at the Battle of Antietam in Maryland, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, declaring that all slaves in territory still in rebellion on January 1, 1863, would be declared forever free. The move was largely symbolic, as it only freed slaves in areas outside of Union control, but it changed the conlfict from a war for the reunification of the states to a war whose objectives included the destruction of slavery.

Lincoln believed that a constitutional amendment was necessary to ensure the end of slavery. In 1864, Congress debated several proposals. Some insisted on including provisions to prevent discrimination against blacks, but the Senate Judiciary Committee provided the eventual language. It borrowed from the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, when slavery was banned from the area north of the Ohio River. The Senate passed the amendment in April 1864.

A Republican victory in the 1864 presidential election would guarantee the success of the amendment. The Republican platform called for the "utter and complete destruction" of slavery, while the Democrats favored restoration of states' rights, which would include at least the possibility for the states to maintain slavery. Lincoln's overwhelming victory set in motion the events leading to ratification of the amendment. The House passed the measure in January 1865 and it was sent to the states for ratification. When Georgia ratified it on December 6, 1865, the institution of slavery officially ceased to exist in the United States.

December 6, 1865

On this day in 1865, the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, officially ending the institution of slavery, is ratified. "Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction." With these words, the single greatest change wrought by the Civil War was officially noted in the Constitution.

The ratification came eight months after the end of the war, but it represented the culmination of the struggle against slavery. When the war began, some in the North were against fighting what they saw as a crusade to end slavery. Although many northern Democrats and conservative Republicans were opposed to slavery's expansion, they were ambivalent about outlawing the institution entirely. The war's escalation after the First Battle of Bull Run, Virginia, in July 1861 caused many to rethink the role that slavery played in creating the conflict. By 1862, Lincoln realized that it was folly to wage such a bloody war without plans to eliminate slavery. In September 1862, following the Union victory at the Battle of Antietam in Maryland, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, declaring that all slaves in territory still in rebellion on January 1, 1863, would be declared forever free. The move was largely symbolic, as it only freed slaves in areas outside of Union control, but it changed the conlfict from a war for the reunification of the states to a war whose objectives included the destruction of slavery.

Lincoln believed that a constitutional amendment was necessary to ensure the end of slavery. In 1864, Congress debated several proposals. Some insisted on including provisions to prevent discrimination against blacks, but the Senate Judiciary Committee provided the eventual language. It borrowed from the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, when slavery was banned from the area north of the Ohio River. The Senate passed the amendment in April 1864.

A Republican victory in the 1864 presidential election would guarantee the success of the amendment. The Republican platform called for the "utter and complete destruction" of slavery, while the Democrats favored restoration of states' rights, which would include at least the possibility for the states to maintain slavery. Lincoln's overwhelming victory set in motion the events leading to ratification of the amendment. The House passed the measure in January 1865 and it was sent to the states for ratification. When Georgia ratified it on December 6, 1865, the institution of slavery officially ceased to exist in the United States.